What You’ll Learn:

In this episode, hosts Andy Olrich and Patrick Adams discuss embracing and celebrating failures, encouraging a mindset shift from a fear of failure to an embrace of experimentation and innovation.

Celebrating failures in Lean promotes transparency, collaboration, and a shared commitment to organizational learning, ultimately leading to more resilient and adaptive teams capable of achieving sustainable success.

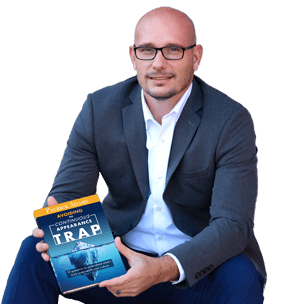

About the Guest:

Mark Graban, author of “The Mistakes That Make Us,” is a renowned speaker and consultant. His other notable works include the award-winning “Lean Hospitals” and “Measures of Success.” Mark serves as a consultant through his company, Constancy, Inc., and also as a Senior Advisor for KaiNexus. Mark is also the host of podcasts like “Lean Blog Interviews” and “My Favorite Mistake.”

Links:

Click Here For Andy Olrich’s LinkedIn

Click Here For Patrick Adams LinkedIn

Click Here For Mark Graban’s LinkedIn

Click Here For Mark Graban’s Website

Click Here For Marks Book: The Mistakes That Make Us

Patrick Adams 00:00

Hello, and welcome to this episode of the lean solutions podcast led by your host, Andy Olrich. And myself, Patrick Adams. How’s it going, Andy?

Andy Olrich 00:40

Great, Patrick, how are you?

Patrick Adams 00:42

I’m doing good. I hear you’re on vacation, South remote location in Australia.

Andy Olrich 00:48

I am I am having a nice time. But yeah, certainly wouldn’t miss this for the world. So thanks very much. Great Debate. Hey, good

Patrick Adams 00:56

deal. Well, let me talk a little bit about the topic for today we’re going to be talking about celebrating failures. Celebrating failures in Lean is crucial. And, you know, it’s it’s an important aspect of fostering a culture of continuous improvement. By acknowledging failures, teams can identify root causes experiment with alternative solutions. iterate towards more effective methods mean there’s just so many benefits by taking time to reflect on some of our failures. The approach encourages a mindset shift from a fear of failure to embracing experimentation and innovation. Celebrating failures in Lean promotes transparency, collaboration, and a shared commitment to organizational learning, ultimately leading to more resilient and adaptive teams capable of achieving sustainable success. And do you mind introducing our guests for

Andy Olrich 01:46

today? Show Patrick. We’re very lucky. Today, we’ve got Mark graven the author of the mistakes that make us book fantastic book butts out now. And Mark is a renowned speaker and consultant. His other notable works include the award winning lean hospitals and measures of success books. Mark serves as a consultant through his company constancy Inc, and also a senior adviser for chi Nexus. Mark is also the host of podcasts like lean blog interview, and my favorite mistake. Welcome to the show. Mark. Great to have you here.

Mark Graban 02:15

Andy, great to be here. Welcome to the podcast and your hosting role here.

Andy Olrich 02:20

Thank you very much. Thanks very much.

Patrick Adams 02:23

Mark, this is not your first time on the show. We’re excited to have you back to the show. Welcome back. And to this new season, obviously, this is our first time with with two hosts. So we’ll see how this goes. And as you mentioned, Andy’s first interview. So excited to be part of this.

Andy Olrich 02:41

Okay, Mark. So the books been out a little while now. So let’s jump right in, I guess, tell us about a mistake that you’ve made recently, or even today. Sure.

Mark Graban 02:50

I’ve got one fresh on my mind from about an hour and a half ago. Thankfully, it’s nowhere close to the realm of anybody being hurt, or losing a customer. So let you know all mistakes are all failures aren’t created equal. This was more embarrassing, and a little maybe frustrating to a couple of people. But you know, there’s a webinar series that I posted moderate through Connexus. Ironically, the topic today was mistake proofing with a presenter, John grout, who is a professor and an expert in mistakes and mistake proofing and the Toyota Production System. A mistake I’ve made before, is in the chat of the webinar, the default says you can chat with host and panelists only. I did not change that default to chat with everybody. So I’m doing things like trying to share a link to the slides. And I even said verbally, I’m going to put a link in the chat. You can click to download the slides. And then I don’t know 20 minutes later, I noticed I was about to reply to something else. And I had replied to someone else’s chat. Like I’m not chatting to everybody. Right? So it was a mistake. And I’m not blaming the people who didn’t call out Hey, where’s the link to the slides like that would have helped. If somebody if you will pull the and on cord and said Mark, you said you were sharing the link, where’s the link? Right? And no, but the thing that’s embarrassing, and it’s a different level of mistake. I think of a quote that I use to lead one of the chapters in the book, Akio Toyota, who had been CEO and is now chairman of Toyota and he said basically, I’m paraphrasing but you know, it’s in Toyota is DNA that mistakes made once or not repeated. And I would try to live by that ideal I would try to set that bar and that standard for myself. So I had made that mistake previously. Along with all the different mistakes I’ve made I’m running webinars and hosting them. I have a checklist that has been populated with the countermeasures and the the attempts if I go down the checklist methodically, I wouldn’t repeat that mistake. And, you know, I think I’m stating fact and not not blaming anybody involved is we’re going through our final prep for the webinar, there had been a hiccup. Technical technical hiccup on the presenter side. That threw me off a little bit. But but but, but that’s the moment when the discipline of the checklist should have saved me. And I lost sight of that, like quite literally lost sight of it, didn’t do it and made a mistake. So there is an opportunity. And a reminder around a checklist is only as good as your discipline in in using it. And checklists are by far, not the most effective form of mistake proofing. So I’m trying to show myself a little gray. So I’ve got a coffee mug here with some mantras on it. And I’m going to remind myself of, okay, be kind to yourself, nobody’s perfect. We all make mistakes, the important thing is continuing to learn from our mistakes. And that when that one stings a little more, because part of the lesson is to continue learning how to learn from my mistakes and not repeat them. So I’m trying to reflect without bordering into beating myself up planned.

Andy Olrich 06:33

Yeah, I think that’s, it’s a great call out. I think everybody listening to this would have had a moment where they have got into a webinar or started presenting and talking about a slides or something. And then someone you know, not being trying to be too polite, but just you know, a lot of people sit quiet. So someone to speak up and say, I can’t actually see what you’re doing there. So and the fact that someone like you can still make those mistakes, Markovic, that gives us confidence that we’re all okay,

Mark Graban 07:01

well, we’re all being humans. So when you say someone like me, I’m like, You mean, I’m absent minded? I’m grown. So I’m like me. I mean, yeah. But that’s where like, we talk about terminology. Like, I don’t like calling something a stupid mistake, because it’s not a matter of being stupid. Smart people make mistakes. We can protect ourselves from mistakes through mistake proofing and checklists. I bet. Yeah. You I mean, Andy, you talked about the I forgot to share my screen mistake. A couple of weeks ago, I was doing a LinkedIn live. And a couple of minutes in, I finally went to go look for the comments. And the comments are like I can’t hear you do. So I laughed at myself and killed the LinkedIn live, went back and tried it again. But, you know, I, and I rarely do a solo LinkedIn live. Right. So if I do it was someone else, they would have caught the audio not working mistake before we went live. So again, you know, learning opportunity. And, you know, back to what you were saying at the beginning, beginning, Patrick? I don’t know if I would celebrate that failure. I think I like the word acknowledging better. It’s not good that the failure was there. But if I can’t acknowledge it, I can’t move forward in a way that hopefully leads to learning and improvement, you know? Yeah, that’s

Patrick Adams 08:31

a good point. I think, for some organizations that, you know, that or have a fear based culture, and they’re trying to shift away from that, you know, it might be something that to celebrate, like, failures, loudly and, you know, but you’re absolutely right. I mean, it’s, it’s still about me, it’s still something that is. But to your point, Mark, if you if you take the time to reflect and learn and make adjustments accordingly, so that it doesn’t happen again, hopefully, that that’s, that’s a definitely an achievement worth celebrating. Right. Sure. Just thinking as you were talking mark, the, you mentioned the checklist, and when we’re mistake proofing, right, we want to try to put some kind of a I like to say you make systems solutions, not people solutions, right. And you know, there’s different types of mistake proofing you know, detection you know, but But what what are so checklist is one of those that isn’t going to absolutely secure you from never making mistakes again. What are some other examples? Maybe, of, you know, pokey oaks are different mistake proofing methods that are more system based versus based?

Mark Graban 09:55

Well, I’ll keep it in the realm of webinars or podcasting. With zoom in particular, I’ve made this mistake was presume, I think was back in the days of Skype in the late 2000s, or early 2010s, the one and only time I forgot to hit record on the interview, you think about how would make you feel if you had to come back to someone and say, I’m sorry, we did that whole interview, and I didn’t record it. So with Zoom, I could have a checklist with the step of like, don’t forget to record, I could put a post it note on my keyboard that says, Don’t forget to record zoom has a helpful feature, where you can set it to record automatically at the start of a meeting, or the start of a webinar. So to your point, Patrick, I would call that a more systemic, a system Poka Yoke, it automatically happens. Now, that does create the risk of a different mistake or failure, where inevitably there’ll be some of that pre go live chat that’s happening behind the scenes. Now in my role of publishing the recording, I would want to not forget to record out that upfront talk. So maybe that the risk of that mistake is not as bad as the risk of not recording. You’re our presenter today, John Brown talked about, you know, sometimes you want to, even if you haven’t made a perfect system, if you can create the opportunity for a benign failure. That’s not as bad as a catastrophic failure. Like he used one example of like, a Poka Yoke on an assembly line, and something’s upside down. So the the line is designed to jam, like that’s a solvable, fixable, non destructive failure, as opposed to something upside down coming through the line, if it wasn’t caught, might crash a machine or create a defect that would affect the customer?

Patrick Adams 11:54

Yeah, yeah. And that just made me think about, you know, risk analysis and taking, you know, for those of us that have utilized P female, or if familia you know, understanding the power of that, and the importance of that, when we’re utilizing that, especially for new processes, or putting new equipment in or whatever it might be, I mean, taking time to actually really assess the potential risks that could happen. And then putting, putting, get being preventative preventative, instead of reactive to put things in place ahead of time, you know, to protect you from that. Things that could could be even, you know, severely could cause death or, you know, harm people, which would be, you know, even greater issue. So, yeah, definitely.

Andy Olrich 12:48

Yeah, understanding and being comfortable with that risk. What jumps to mind is two things is some pieces of equipment, for example, might have a shear pin or something that is designed to fail, designed to break so that that larger catastrophic thing can occur. And, and people are comfortable knowing that that’s there. And that exists. But we prefer that to, you know, if we didn’t have that particular failure point in there built in. The other thing, Mark, just a bit of fun. When I said people like you I really met somebody very experienced and does this quite often is a Have you got any room on the other side of your coffee mug for the checklist, you’re talking about your affirmations.

Mark Graban 13:26

The checklist was either a spreadsheet, or sometimes I printed it

Andy Olrich 13:29

out. But I might be doing two selections. I mean, the

Mark Graban 13:33

checklist is too long to fit on the coffee mug. By the way, this coffee mug has a broken handle because of a shipping mistake made by the vendor. I have these custom mugs made with my affirmations on the back reminds trying to remind myself be kind to yourself. It also applies to be kind to others, including the company that shipped me, I think like 10 Coffee mugs, and four of them were broken. Oh, geez, they hadn’t been packaged correctly. And they all broke on the handle well, so in the name of good customer service, they apologize. We’re so sorry, we’ll send you for replacement mugs. Two of those were broken. At least we’re getting close. Improving. But I started using a different vendor that can print the same quality but has more reliably packaged them. So even though they tried to make up for it, I eventually took my business somewhere else. Right?

Patrick Adams 14:28

Well, that’s a good example of, you know, allowing the same mistake to go through multiple times and you know, the ripple effects of that down stream for you know, our customers or whoever that may be. I mean, it’s obviously an important aspect of continuous improvement. In I just was thinking as we were talking about the the machine or the the risk of putting something a solution in place that could cause other issues or harm or whatever it may be. That’s physical harm. We were talking before we hit record about psychological safety. And you You had mentioned an article that that Mark wrote, I haven’t had a chance to read it yet. But any thoughts on the article? And how that could tie in with what we’re talking about today?

Andy Olrich 15:17

Yeah, so the article I was referring to was on Mark’s blog, and it was around how, you know, if you don’t have good psychological safety in place, it can be deadly. And it was, it was referring to an example in the airline industry. But Mark, would you be great if you could talk a little bit about that, please?

Mark Graban 15:35

Yeah, I mean, it was something that I had written him reacting to, in response to a really long investigative piece in The Wall Street Journal. This is, you know, after the January 5, incident where, in layman’s terms, you know, part of the size of the plane blew out at 16,000 feet early into the flight. Nobody was was killed, thankfully. But you know, there’s this door plug. And it, people think, loose what’s being said publicly as that there were some bolts that had not been properly tightened. That led to it coming loose and being jostled in some turbulence, perhaps in it in it flew out, and the pilots are able to land safely. Speaking of checklists, though, the cockpit door supposedly popped open. And I watched one video have tried to take some really deep dives into industry, people talking about all of this, that there’s supposed to be a panel that pops open by design to even the pressure between the cockpit and the back of the plane, both doors not supposed to pop up. And that’s now a security risk. But some some safety checklists and emergency checklists were supposedly also sucked out of the cockpit. So they were having to work off memory and I would call what they what they did heroic, but on the manufacturing side, the Wall Street Journal had this piece, the headline was this has been going on for years, inside Boeing’s manufacturing mess. And there’s there’s lots of stories about and I’ve read this in other places, quality inspectors getting in trouble for doing their job, like, Hey, we’re pointing out problems. And someone I’ve worked, you know, started my career at General Motors, when it was not a Lean culture. And the pressure was for quantity and production speed over quality. It was not a stop the line to do it right. The first time, culture, there are things said about Boeing that kind of remind me of that GM culture, even though Boeing would say they’ve been implementing Lean for decades. But back to one other thought on the psychological safety thing. You know, psychological safety means that we feel safe to speak up. pointing out problems admitting mistakes, I’ve got an idea. disagreeing with the boss like psychological safety doesn’t mean I’m free, free from being disagreed with like, Hey, don’t don’t disagree with me, Patrick, because you know, psychological, my psychological safety like that’s, that’s not how it works. Because of your psychological safety. Patrick, you should feel safe to speak up to me. So there’s this question of do people feel safe speaking up about defects? So let me just read this one story. As I wrote about, like, I literally knew what the punch line was, because I’ve seen this and been through it. So it says, spirit Aerosystems employee, and this is who makes the fuselage and initially in store installs that door plug, they threw a pizza party for employees to celebrate a drop in the number of defects reported that that word I hear you go in magic that word defects reported. That’s not the same thing as the actual defects. Right? That’s why That’s why you’re going huh? Yeah.

Patrick Adams 19:04

Anyway, as soon as you read it, so

Mark Graban 19:05

then so here’s the punchline of the story. Shatter at the party turned to how everyone knew that the defect numbers were down, only because people were reporting fewer problems.

Andy Olrich 19:18

Worse, good score, basic, good play a high.

Mark Graban 19:21

I mean, so there, I think a lot of the focus is either on I mean, I’ve seen somebody who wrote literally, and this made me throw up a little bit. You know, somebody was trying to be tongue in cheek, they said, You know, I don’t want to die because some idiot didn’t tighten the bolt. I’m like, that’s, that’s not cool. Like, the problem is not some idiot. It’s far more complicated than that probably comes back to culture. And some would say, well, that person just needs to do their job. And like, are they given the right tools? What’s the inspection process? Are they under too much pressure? I mean, there’s so many other factors then You just do your job.

Patrick Adams 20:01

Yep. Yep. And different. Yeah, no, no, I, there’s so much to unpack here. It just it it made me think about a story that Mr. Yoshino when we were over in Japan with Katie Anderson on on the Japan trip over there. He talked about it. This is in Katie’s book as well, but a story when on the paint line, and I’ll probably not be able to give all the details exactly. But basically what happened was, you know, he he allowed a mistake based on the work that he was doing on the line in it while he created a problem. And he stopped it pulled the and on cord pulled the line said stop, there’s an issue and thinking to himself, I’m about to lose my job, you know, because I just stopped a lot and automotive assembly line. Well, he feared that you didn’t know what he was a young engineer knew, I think he was at this time fairly new to to Toyota. And so he wasn’t sure what was gonna happen. And they came to him and thanked him and celebrated that he pulled the line and apologized to him that they allowed him to be able to make this mistake, because they that’s in their mind. That’s disrespectful that systems were not set up for him to be successful. Right? I mean, we have to think about we should never see on a root cause analysis form or a solution that we’re retraining operators that it’s the operator. So, right. It’s just that’s not the case. What are the system? Where was the breakdown in the system? Right. That’s what we have to ask ourselves.

Mark Graban 21:39

Yeah. Right. And that story was so vivid. Katie was so great to line up, Mr. Yoshino to come on the My Favorite mistake podcast with with me with her. He told that story, a version of that story is in my book, the mistakes that make us it’s broken. Did you know that story was 1960s, Japan, its book ended by a story told by my friend David Meyer, who started at the Kentucky Georgetown plant. We’ll call it the late 80s. Sent the paint shop, it was a bumper part molding line. But if so it was the wrong chemical added to a machine. And the reaction was very similar of we didn’t set the system up. We didn’t set the workers up for success. You know, I’ve heard I love the expression. I always say Darrell Wilburn Buncher. He heard it from a lot of other Toyota leaders, that it’s the leaders responsibility to design a system in which people can be successful. That doesn’t mean perfect system, right, there’s always room for kaizen. But how are you supposed to guard against so I put the wrong chemical in the machine. But that wrong chemical wasn’t even supposed to be there? Right, it was a supply chain and materials issue probably more at root. And it’s like it’s unfair to ask people to be on guard for a mistake that has never happened to you or isn’t part of the standardized work. And, you know, you can mistake proof the design of the barrels so that they’re more visually dissimilar. Same opportunity in healthcare with medications and mix ups that occur in a pharmacy, or in a nursing unit. So yeah, big opportunities for mistake proofing. All sorts, but with maybe say one of the things Sorry, I’ll be giving a TED talk here, but different types of mistakes or failures. Like so. Mr. Yoshino was talking about his process failure. And I think that’s a different kind of failure or mistake than what you were talking about earlier in terms of innovation, or improvement, where when you’re innovating or improving, doing something new for the first time, I think you have to expect to fail. And then to what you were saying celebrate it and a lot of my podcast guests have talked about that culture in their company. It’s hard to mistake proof a bad decision. But we can mistake proof, a fairly regular repetitive process. Well, that’s whether that’s painting a car or running a webinar. And I think that’s the difference between mistakes that we really try hard to prevent, versus the ones we want to sell, discover and learn from and celebrate, but Either way, psychological safety is required for people to speak up about either type of mistake.

Andy Olrich 25:07

Yeah, and I think, again, why it really resonated with me Mark is I spent some time working in underground underground coal mining, okay. And obviously, personal safety was was number one. And we actually had a poem shared with us from they told us it was written by a coal miner in the US somewhere. And it was called, I could have saved a life that day. But I chose to look the other way. And that was his whole story about how he didn’t want to speak up. And he’d done that similar thing before, and so on and so on. Anyway, in this case he’s made didn’t come out, they come out of the mind at the end of the day in good shape. So that was, again, and you said a lot more now. But yeah, there’s there’s such a Yeah, obviously, importance around quality and workplace satisfaction. But the it’s, it’s real, it can turn quite, quite bad, quickly if we don’t have those things, and people are comfortable to speak up. So I really appreciated that article.

Patrick Adams 25:55

Thank you. Mark, what would you say? We’ve talked a lot about culture here. But I mean, what do you what factors? Do you think organizational culture and leadership play? You know, in this, this whole topic of creating a culture where people feel safe to to make mistakes, or, you know, take the time to reflect and learn and adjust, you know, as they go forward? What role does this leadership play in all of this?

Mark Graban 26:27

A major role and it arguably starts with whoever’s at the top of the organization owner, plant manager, CEO, what have you, I’m really fortunate to have taken some formal training and certification through a company called leader factor. The book, one of the key books about psychological safety. And I’m having a complete brain cramp on the four stages of psychological safety. Oh, my goodness, here’s another mistake. Okay. That’s a total mid afternoon brain cramp Timothy Clark, my goodness, I’ve interviewed him and talked and written about him so much, Timothy Clark. So I think his research is really insightful and helpful and that there’s really two key countermeasures, right? Here’s a short list. Leaders need to model the behaviors that they want to see. And then reward people when they take a chance at following their lead, right. So I’ll use Connexus, as an example. And we’ve done formal surveys that kind of confirmed I think, our sense of it, that it’s a pretty high psychological safety, culture and employees will say so and compared to other places that they’ve worked. It’s an environment that doesn’t punish people for speaking up it better than just tolerating it right, you have to reward it and celebrate it. So I think part of that culture, I share stories about like about this in the book, co founder and CEO, Greg Jacobson, Greg is very willing to admit when he was wrong when he made a mistake, not to shame himself, right? You know, we’re not ridiculing him, What’s wrong with you. But I think that openness, sets a really good tone and sets a very practical example. And I think setting that example is more effective than just encouraging people. I want you to speak up actions matter more than words. So when the leader speaks up, and then someone else on the team admits a mistake, and he reacts positively to that, now you start getting a positive reinforcement happening there. And there are times in the weekly team meetings, someone will share a mistake. In the spirit of Well, hey, I want you to learn from me. And let’s talk about ways of preventing that mistake. And, you know, no one’s ever getting teased, or formally punished. I think it starts with leadership and gets reinforced to different levels down to the frontline staff.

Patrick Adams 28:59

That’s right. Andy, if you don’t have a question, I have another question.

Andy Olrich 29:04

chilka. All right,

Patrick Adams 29:06

I got one for you mark. This as you were talking, I was thinking about a specific leader in an organization that maybe is a little bit the opposite of what you were talking about. And I remember him leading completely with fear based, like, I want to instill as much fear into my team as possible. And in hopes that they will never make mistakes. And I just remember man, when not on the production floor, everybody would completely change the way that they were working because they want to be good and not get yelled at or not having stop and talk to them. I’m sure others that are listening right now are probably resonating with this or no, you know, either have worked at companies or know leaders that that lead in that way. For those that are listening, that maybe work at an organization where they have a leader that beats like that, I mean, any recommendation, any suggestions to them on? You know, how do you continue to make improvements to try to make an impact in the area that you know that you’re that you have control over? When you work in an environment that is almost the opposite of what we’re talking today.

Mark Graban 30:20

So somebody like that has been put in a really tough position is as much as I admire people for speaking up in risky or dangerous workplaces that way. And I mean, like, psychologically unsafe. Like, that doesn’t scale well, like no matter how bad the environment, there’s always somebody who’s still willing to speak up. It might be someone who’s planning on retiring in two months. So like, yeah, what do I have to lose? That changes their dynamic of thinking through? Should I speak up or not? And I would never, I tried to address this in the book, I would never want to lecture people and say, like, you should speak up. Or to frame it sometimes as like, well, you should be courageous or, you know, people with high character, speak up about it? Well, I don’t think that ability to speak up is a matter of courage or character. It’s a function of culture. And so I look, you know, sometimes people need to just protect their paycheck, protect their family, protect their house, the roof over their head. Anyway, I don’t say this flippantly, I think there’s times when people should keep out of trouble. If the culture and your leaders are not welcoming the disagreements or the speaking up, then you know what stops speaking up. Now, that creates a situation like the poem, which I want to go and read, write of, I could have saved the life today. But I look the other way. Somebody still might feel really guilty for being involved in a situation that maybe wasn’t completely their fault. They get in trouble for speaking up, they stop speaking up, and then somebody dies, like who wants who wants to live with that? On their conscience? So I mean, I say this not trying to sound flippant, but sometimes you need to quit and find another job. And I know that’s not always practical. Someone might be locked in on a pension that’s coming. And again, it’s like, yeah, just you hate to see people in a situation where it’s just a matter of trying to get by and survive and keep out of trouble.

Andy Olrich 32:32

Right? Yeah, I

Patrick Adams 32:34

think you also have to, like, to your point, I mean, you have to protect your own mental health. And, you know, and that same time, balance that with being able to pay your bills, you know, so So that’s a that’s a really difficult situation. And I just, it made me think about it, because I, you know, a couple of individuals that worked at that company, I really, my heart went out to them, because I just, I knew the difficulty of making a change to an Executive leader like that, obviously, you know, we, we had some conversations, and I was completely candid and real with that person about what I was seeing and experience and hearing. And yeah, I guess I was just curious, because, you know, I know that that that that happens, and there are individuals out there that are working in organizations like that. It’s a tough place to be in for sure. And yeah, I don’t know. Do you have any any thoughts on that? Or? Yeah,

Andy Olrich 33:28

it’s, it is a tough one. And I really, I really do feel for those people who may be right in that situation now and listening. And, yeah, it’s one of those things is, there’s this phrase that we use, or a description we use here, I don’t know whether you’ve heard of it, but it’s called the ducks on the pond look. And what that talks about is, if you’re walking around with a leader, or you observe a leader walking into a work area, and all of the people immediately start to move away, like you said, they start to change how they’re working, they’ll seem to go over to a far corner, like the ducks on the pond of view. They all start to scatter, but just very quietly, that’s like, oh, okay, what’s what’s happening there or? So? Yeah, there comes a point where, if you can pull yourself up a level from that I’m getting in trouble. It’s more like, Hey, someone could die here or another person is struggling mentally over there, and someone’s got to speak up and we have but I know a lot of people are quite proud and they don’t want to come across as like, again, what we call down here are winter. You know, someone who’s always speaking up, it’s always the one person who’s seen as a complainer and a whiner and then we just pretty much ignore everything they say at times too, because they’re constantly speaking up. So it’s a real Yeah, it’s a real challenge for people but if you’ve got to feel safe, and that’s where the leaders like you said it starts at the top and if they’re, if they don’t get feedback regularly, they they see that as a problem and some places are working have measures if the employee suggestion scheme is tapering off, hang on Well, hazard identification is tapering off. Yep. Yeah.

Patrick Adams 35:03

Sure.

Mark Graban 35:04

I mean, I’ve seen organizations that have celebrated. I’m gonna bring up the word reported again. And healthcare, the number of reported incidents was increasing. And why is that a thing to celebrate? Because they were closing the gap between actual incidents and reported right now that gives you a fighting chance to see the impact and the harm rates start going down. Right. So and for a lean audience, hopefully this resonates with people, you need more than psychological safety. Right? That eliminates the fear factor of what why do people not speak up, it’s often because of fear. If people do speak up, and they get thanked, and nothing else happens, people stop speaking up for another F word futility. And I’ll say Ethan Burris, I didn’t have a brain cramp on him. Ethan Burris, University of Texas, Austin in his research, without good problem solving, you know, the futility factor kicks in. So I think a lot of people in Lean land have done so much training and emphasis on problem solving. I think the bottleneck is often psychological safety, or the lack thereof. So speak up. psychological safety, then use problem solving to put the issue to bed. So you’re not having to be kind the next time the same mistake is made again.

Andy Olrich 36:22

Yeah. And I think in the Lean space, too, with the visual management supporting the structure around that people have a structured way of capturing that and it flows down into a problem solving or a visible five why’s underneath each of those, like, it’s that’s where I find that the visual management of Lean is really powerful, because it’s not how I would describe a problem as opposed to someone else, we can find a standardized way to capture and measure and see it all in one place. I think that’s yeah, that’s really where when I’ve worked in Lean organizations, it’s a psyche, art, and it’s all there. There’s nowhere to hide, if that one’s not closed off, we see that and hang on. This is important to someone. Yeah, this is their voice. Yeah.

Mark Graban 37:00

But let me share one other thing real quick that I think, you know, lean audience might appreciate, maybe trying to think through of speaking up as a function of culture. So you might have people who are have been bullied into not speaking up at work. But when they go into a meeting with the teacher, or they go do something at their church, they’re speaking up all the time, while they’re making suggestions, and it’s being rewarded in those settings, so they’re going to keep doing more of it, then they come to work. And it’s very situational. They’re not a different person. But they’ve learned to adapt to maybe a nasty workplace and the thought experiment, which I’m curious if if it’s ever happened in the real world, you take someone who had worked, let’s say 20 years at Toyota, Georgetown, and they had to move to Michigan because of family. And I don’t have this be they go get a job at one of the Detroit automakers that also had physical and on cords. But maybe it was still back in the era when people would get yelled at for stopping the line. I bet that Toyota person would learn very quickly to develop new habits. Same person, different culture, they’re going to act differently.

Patrick Adams 38:09

So true. Yeah, that’s such a great point. And and yeah, I’m sure that happens all the time. It’s such an important reason for as leaders for us to look at our culture first and understand that that we need to make adjustments to the culture and put a lot of effort into, you know, changing that piece of things before we try to throw you know, tools out there. So great, great. Marquis, that so the books been out for a number of months now. How’s it how’s it going? Our sales? How’s how’s the traction of the book? Are you hearing feedback on it? What, what’s been happening? Yeah,

Mark Graban 38:46

so I mean, as of this recording books been out a little bit over six months now, the reviews have been pretty positive, it’s hard to find a book that ever has full five star reviews, then you only you only hope that the reviews that aren’t five star have something constructive or useful in there, but I think the response has been good. Doing more webinars and speaking engagements related to the book and, you know, I think there’s this opportunity to help with one or both of these these two pieces of psychological safety or, and or problem solving. I think they go hand in hand. I think there’s bigger opportunity, you know, to try to help bring people up to speed around not just the psychological safety concepts, but what we can do to help cultivate that in our workplaces. So yeah, I mean, I, you know, I It’s hard to answer that question of like, well, what do you think about the sales I’m always trying to figure out how to get the word out and I think the books good enough to publish and not perfect and, you know, there’s there’s things I look back and like, Oh, I could have said that more clearly or what have you but, you know, thinking evolves. I tried to keep learning I kept talking to new people who inspire me. Figure out how to get better at learning from mistakes and help others do the same.

Patrick Adams 40:09

Well, I’ve seen the book in many people’s hands, and I’ve heard all good things. So it’s definitely one that everybody that’s listening in should get a copy of, we’ll drop a link in the show notes. So if anyone’s interested to grab a copy of Mark’s book, there’ll be a link in the show notes. And then as always, we’ll put a link to your website and your LinkedIn. And so if anyone has a question that want to reach out to mark, feel free to grab the contact info out of the show notes and in reach out. So Mark, it’s been great to have you on. Once again, light love checking in on you and just kind of seeing how things are going with, with your your book and speaking and just love the work that you’re doing and helping to you know, positively impact the Lean community. So thank you for that. Appreciate you being on the show. Thank

Mark Graban 40:57

you, Patrick, and welcome aboard Andy. Thanks for diving into this.

Andy Olrich 41:01

Thank you very much. And yeah, really important topic and good on you. It’s great to chat. Thanks. Thank you both.

0 Comments