What You’ll Learn:

In this episode, hosts Patrick Adams and Catherine McDonald discuss the common mistakes emerging leaders often encounter. It’s a conversation that highlights the transformative power of errors, turning them into stepping stones for future leadership excellence.

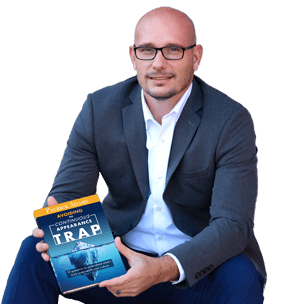

About the Guest:

Phil Ranck, a retired 24-year United States Army veteran from Pennsylvania, excels in Lean Six Sigma methodologies, holding certifications such as Certified Department of the Army Master Black Belt and accreditations from IASSC, ASQ, and CSSC. With a background in Military Management and program acquisition, coupled with a Master’s degree in Transportation and Logistics Management, Phil has trained numerous students in Green and Black Belt Certifications, leading impactful projects. His commitment to clear processes for change is reflected in additional certifications in Design Thinking, Business Process Re-Engineering, and Change Management from institutions like IBM, IDEO, and Virginia State University. In 2019, Phil founded Lean Alaska upon retiring from the Army, focusing on delivering quality, personalized interactions and fostering a community of Lean Six Sigma practitioners.

Links:

Click Here For Catherine McDonald’s LinkedIn

Click Here For Patrick Adam’s LinkedIn

Click Here For Phil’s LinkedIn

Click Here For Lean Alaska’s LinkedIn

Click Here For Lean Alaska’s Website

Patrick Adams 00:32

Hello, and welcome to this episode of the lean solutions podcast led by your hosts Catherine McDonald and myself, Patrick Adams, how’s it going? Catherine?

Catherine McDonald 00:39

I am very well, Patrick. Thanks.

Patrick Adams 00:42

Good. Well, I’m excited about today’s topic, we have a new guest on the show that’s coming in all the way from Alaska. And we’re going to talk specifically about mistakes that young leaders make. So, you know, in conversations centered around emerging leaders, we always talk about these these common mistakes that that are often encountered, especially with young leaders who are who are, you know, either new to the organization, or maybe they’re emerging leaders that are that have been promoted, and are now starting to rise up in the company. But, you know, from from striving for perfection, to learning how to embrace errors, the journey, the leadership journey, reflects X aspects of growth and resilience. And the discussion today is going to blend the insights of experienced leaders with the enthusiasm of emerging ones. We’re going to illustrate different mistakes and talk about that in different industries, including the military, which Phil is, is a 24 year veteran. So so I’m excited to have him on the show. But the conversation is going to highlight a transformative power of you know, errors of turning them into stepping stones and then future leadership. Excellent. So I’m super excited about today’s discussion. It’s going to be a lot of fun. And we’re going to talk about some really cool stuff. So Katherine, do you want to take a minute and just introduce Phil to the show?

Catherine McDonald 02:06

Yes, I would love to. So as you said Patrick failed rank is a retired 24 year United States Army veteran from Pennsylvania. He excels in Lean Six Sigma methodologies and holds certificates such as the certified Department of the Army master black belt, and he holds accreditations from iassc, the ASQ and CSSC. Very impressive. With a background in military management and program acquisition coupled with a master’s degree in transportation and logistics management. Phil has trained numerous students in green and black belt certifications. And this has led to very impactful projects. So his commitment to clear processes for change is reflected in additional certifications in design thinking, business process reengineering, and change management from institutions like IBM, IDEO, and Virginia State University. Where do you get time to work with all this study, I decided, in 2019, failed by and lean lean Alaska upon retiring from the army, focusing on delivering quality, personalized interactions, and fostering a community of Lean Six Sigma practitioners. Welcome to the show, Phil, thanks

Phil Ranck 03:22

so much as I’m listening, you say that I’m asking myself the same question and then realizing like, wow, that makes me sound a lot smarter than I really am. Like, it doesn’t happen bio is, oh, by the way, list all of those mistakes that we were talking about those different techniques. So yeah, I think that highlights the positives, for sure. But, but thanks for that. I appreciate it. Yeah,

Patrick Adams 03:43

that’s, that reminded me of a picture, Phil, that I saw, I think it I don’t know if it was an iceberg or something where, you know, you see the the success at the top, but you don’t see everything underneath it that it took to get there. All the failures, all the learnings, all the development, all the struggles, all the challenges, right, that actually took you to get to the point where of what people actually see now. Yeah,

04:05

yeah. And it’s funny how that works. So that I’d love to say that all of those things were, you know, like, Oh, I just, I want to be better. I want to, you know, I want to I want to I want everything, it wasn’t a matter of desire that drove me in all those it was more of a question or again, answering something where it was, it was simply curiosity that drove me to all those areas, you know, I see you have this over here, and this over here, but I don’t understand where they come together. So I just start learning in I start just trying to understand the differences. And then I get questions again, as we’re going to talk about today from leaders. And you know, it’s really hard to mentor a leader if you don’t have the background and understanding yourself. So, you know, as we’ll talk about, I teach, I train I, I certify, and one of the biggest questions I get is, well, what’s the difference? What is process improvement? And what’s the difference of all the things that are in there? And, you know, we use these terms, well, where are the parallels, where are the separations and I was like, Well, I guess Ready to Read a book? Or I’m not gonna be able to answer that question really well. Right.

Patrick Adams 05:03

Right. I love that you hit on that, that the point about having experience to back that, you know, when you’re teaching when you’re coaching someone, fortunately, there’s a, there’s a lot of consultants or coaches that are out there that have a lot of they’re very book smart, they’ve read a lot of books, they’ve, you know, they’ve maybe attended a couple of workshops or things like that, but they don’t have the experience that you know, the boots on the ground of being there in the trenches working through these things and experiencing what you’ve experienced. And, and Catherine and I have experienced and many other practitioners that are listening. And that’s that’s unfortunate. Right. So you know, but I love that the the fact that you pointed that out as an important part of being a good coach is the experience part of it, of actually going and trying for yourself and learning. It’s an important for sure. Phil, before we dive into the conversation today about young leaders and mistakes that young leaders make, and how do we How does process improvement help with some of that? I want to talk about Lean Alaska, because I think everybody loves Alaska, when you hear the word Alaska, you know, people’s ears perk up and, and they want to hear more. I’ve been to Alaska a number of times you and I’ve talked about this, and it’s just an amazing place. And you mentioned to us before we hit record today that this is your favorite time of year because the sun is shining, it’s warm out, but you can still get your snow machine out which in Michigan, we call snowmobile snowmobile snow machine. Both of us are snowmobilers. But tell us what it’s like they’re in Alaska right now, this time of year. You

06:46

know, it’s just beautiful. And I think the one the biggest thing about Alaska is, is the diversity of the seasons. You know, you spend six months in winter, and you spend six months well, not really six months, it’s like four in summer ish. But there’s such a stark difference in winter, it’s almost 24 hours of darkness in summer, it’s 24 hours a daylight. So this time of the year, especially now that we just had the daylight savings time. Like it doesn’t get dark here, it’s almost 930 At night, and then it’s light again, by six here in about a month, it’ll be 24 hours of daylight for us. So there’s still snow on the ground, there’s still snow capped mountains. And you can still do winter things without freezing to death. Because it’s you know, we’re at we’re right around the freezing temperatures. So as I mentioned yesterday, you know, we got done class and the freedoms that come along with retirement as well as, you know, being able to walk away from what we’re doing. And we all hopped on our snowmobiles, or we call them snow machines here. And we took about a 25 mile ride out to a glacier. We took a picnic where this went to an Ice Cavern had a really nice picnic as a family, and then came home. And when we got home at nine o’clock at night, you know, it’s still daylight out. So I mean, those are just, those are just day to day adventures in Alaska. Wow, I

Patrick Adams 07:54

love it. Love it. And I think we’re going to talk obviously, we’re going to dive into process improvement and those types of things. But I want to before we do, I want to just hear a little bit more about Lean Alaska, because this is obviously you live in Alaska. So that makes sense. But tell us just a little bit about what Lean Alaska does. And you know, what was the motivation behind it? How did you start it? You know, kind of what types of things are you guys doing? Just give us an overview.

08:25

So yeah, you know, try to make it a real short story. I never set out to run a business, it was actually kind of a mistake that it actually started. So again, in the military, and we’ll talk about that I spent 13 plus years doing process improvement, or Lean Six Sigma, I served as a master black belt, which, you know, had various different various roles and impacts. But right around two years before I decided to retire, I was here in Alaska, and I was buying a book because I was teaching a Greenbelt class. And when I was buying this, I was buying multiple, so we only have one Barnes and Noble in the state, so not a lot of places to go. So I stopped by there. And they asked why I was buying so many books to a conversation, I had a few people asking me if what I did translated or could help them with their small businesses. Because then, you know, ask is, is very well known for its small businesses? And I said, Well, yeah, I mean, there’s a lot of these techniques that would apply. It doesn’t have to be done at scale of corporations that can help any kind of, you know, a bit, you know, process improvements, process improvement. And so they ended up taking my phone number and calling me back. So I started consulting before lean Alaska name even existed in real consulting, I was just helping, I was taking what I knew, and supporting and then that lightly trans I was like, well, somebody has told me at some point that like, Phil, you’re gonna need a business license. I’m like, What’s that? They were like, Oh, you got to fill out this paperwork. I’m like Google paperwork. I do that all the time in the army. I’m good at that. So I kind of followed that path. And lean Alaska grew basically out of necessity in Alaska. And then as I retired, that translated into more consulting and then the consulting led to my soldiers still calling back Hey, Are you still training? Well, not in the army anymore. Let me figure this out. And I figured out how to train soldiers again. So lean Alaska just kept growing out of necessity. So now I spend 70% of my time training and certifying primarily soldiers, a lot of industry is in there now as well, because the other 30% of the time, I still consult, but but lean Alaska, came out of that necessity for small businesses and then medium to large sized businesses in the state trying to figure out how do we do better with the limited resources we have, you know, it’s a unique entity, we don’t have a railroad that comes in and out of the state. So anything that comes to us is either by barge or by air barges very slow air is very expensive. And, you know, we don’t have a lot of natural resources that that a lot of that most have access to. So how do you overcome those complexities and those limitations? In comes process improvement?

Patrick Adams 10:52

Wow, I love it. Yeah, that’s great. I love that you saw a need, and you filled it in. I mean, so many small businesses in Alaska are so thankful for Lean Alaska and the work that you guys are doing. So, you know, thank you for that. I appreciate it. And while I’m on that, thank you for your service, by the way, 24 years in the United States Army, very much appreciate that, as well. And obviously, you know, there’s not a lot of people that we get on the show that have applied that have been a master black belt in the military that are applying process improvement in the military. So I’m really excited to hear some of your experiences. And obviously, you know, when you enlisted in the Army, as a young soldier, you you didn’t know about Lean, as far as I know that you were introduced in the beginning, but I’m sure you made lots of mistakes, just in applying process improvement or learning process improvement, but mistakes in general in the army. And as you’re learning as you’re developing yourself as a leader, can you talk to us a little bit about, you know, some of those mistakes that you made as a young leader, and then later on how maybe, as you started to learn about process improvement tools and techniques, how that maybe helped to, you know, not necessarily repair the mistakes, but help to you to be able to maybe mentor others in who are experiencing some of the same things or how was processing room enabled able to help?

12:17

Yeah, last guy, but we we need probably motivated, we need a month of podcasts to cover the mistakes that I made as a young soldier. I mean, wait, yeah, when I came in, I joined the army when I was 17, I and I lived in a very small town in Pennsylvania, and it just wasn’t a lot there. So it was a very big world. And when I when I went to my first duty assignment in Alabama is the first time I had ever left my state. So it was very new world to me, different culture, different people. But as a young soldier, mistakes were bound and I was a young mechanic, I didn’t, I joined the Army to do something I understood how to do which was work on cars, that was my my background, and all the mistakes on mistakes Well, and what mistakes were made. You know, when we talk about process improvement, I had no idea what Lean Six Sigma was back, then I’m not even sure it was around. I was I’m getting kind of older now. But it was around, I just didn’t know what it was. Right. But I suffered from that. And my leaders suffered from that from my actions, even before I became a young leader, you know, my mistakes impacted them as leaders. And what was interesting, and I didn’t realize it, then until you look back at it now was I made mistakes. Well, the guy next to me made mistakes, and the guy next to me made mistakes, and the guy next to him made mistakes. And that’s four different parallels of everybody doing something differently that these leaders had to react to. But when I was a young soldier, we always you always kind of take it a little bit personally, you’re like, Why am I always getting yelled at for this? I don’t understand. Because we as young soldiers didn’t understand the complexity that the leader was dealing with, right leaders aren’t responsible for one person, they’re responsible for the masses for all of us. And, you know, as soldiers, they weren’t just responsible for our day to day actions at work, they were responsible for our home lives, I was 17. These were like my surrogate parents at this point. And leadership took on a different leadership and I say the word leadership because it will talk about parallels in the words manager leader and leadership later, it was very different. I had leaders that I had those that were in leadership, you know, that were leadership to me and sometimes they weren’t the same person. So you’ll and I didn’t realize things even you work in process improvement. I worked in motor pools. So if I forgot a wrench or a toy, I’d have to walk back up to the motor pool and walk back down to the line when you’re walking back and forth. What do you think I got yelled at for rank. Why is it taking you so long to fix that truck? Well, because I’m an idiot, I keep forgetting my wrenches, right. So we just aren’t will will work faster and their solution to that was run instead of walk wasn’t like, Hey, dummy, cord it to your way so it drags along with you. It was just move faster. So I started to recognize those and as I got into that that NCO role, which for us noncommissioned officers was that leadership role or that leaders role. I started to understand from those myths Ah, like, oh, yeah, you know what, I should probably tell him to do this a different way, I remember why I got yelled at. So let me take a different approach and understand it from their perspective, having a trench. And then I made this, you know, and I was an NCO for a period of time when I started, really getting into leadership, if you will, when we get into those first deployments 2001 2003, when Iraq and Afghanistan really became a thing again, here, I am young, you know, early 20s, responsible for taking them through a combat situation, and, and that’s when mistakes were really critical. There was no room for mistakes. So the question became, how do you anticipate making these mistakes? Well, the only way to anticipate a mistake is probably to have some experience in that. And one of the things I learned very quickly as an NCO was, my experience was limited to my actions. And I understood as a leader that I needed to talk to everybody around me to understand what they experienced. So I could capitalize on that kind of like voice of the customer, right? And you need to know what everybody else knows on the team. And then I made this shift about mid career from an NCO to a Warrant Officer, which I became more of a program director, I think is probably a more apt description, where I will focus specifically on processes and programs for an organization I became an advisor, oh, like a consultant for the army. Again, I had to start over, you know, I had spent all those years becoming a leader as a noncommissioned commissioned officer, when I became a Warrant Officer, I was a new guy again. But I had to learn leaders, leadership roles and leaders requirements from a whole new perspective, which allowed for all new mistakes. And those mistakes were too many assumptions. I assumed that I knew what everybody needed to know, as opposed to clarifying what I needed to know. Overconfidence was a mistake that I was making. I was overconfident sometimes in the answers that I was giving without any kind of really validation of any kind, and assumptions and overconfidence, being my mistakes led to the ability for those below me to make mistakes. And then the other mistake I made, as you can see, these compounding was not recognizing that their failures were due to the mistakes that I was making as a leader. And how I was directly they were looking to me for the answers, my answers guide their actions, if their actions resulted in something less than I was expecting, at that time, free process improvement. I didn’t understand that dynamic very well. And then as I grew, I was a logistician. And I spent all my time in the military in the tactical world. I started jumping out of airplanes when I was 19 years old. So the army just kept throwing me out of airplanes for you know, 20 plus years. So I spent a lot of time in this tactical realm, meaning I was always at the forefront. I was always where the fight was happening, kind of a thing. And my support as a logistician was always to the infantry meant that you would see right, those really in harm’s way. So again, mistakes matter. As a logistician. We provide the capability for them to do their to do what they do. It’s like watching poetry in motion. These guys were amazing. But they kept coming back. And they were like, Where are the bullets? Where is the fuel? Where are the parts you logisticians are horrible. And I kept looking at and I was like, man, but the look, but the people aren’t your problem. It’s the process, you’re a lot faster than we are. Because we’re relying on outside entities. You know, we all know how the global supply chain works, but an infantry world that didn’t matter. So I kept saying to myself, There’s got to be a better way. And that’s when I got introduced a process improvement. Process Improvement taught me not only taught me to look at a process instead of the people having the mistakes, but it also taught me how to educate my leadership, my leadership at that point, to understand like, hey, when you’re complaining, because I can’t get you something fast enough. It’s not because I’m slow. It’s because the process that I’m using, and the, the, you know, the space that you’re giving me to operate, and they don’t line up. And that’s not because I personally didn’t do something that needed to be done. It’s because we haven’t communicated properly to close that mistake, gap, kind of a thing. So that’s how I got in the process improvement was I wanted to support my operators better. And I had to learn how to improve a process like you can’t, you can only improve people so much, there’s so much noise factor in there. You can tell a person to do something all day long. You can’t force them to do it. You can’t change their minds. So you create a process that enables them to hopefully focus themselves the right way. It’s a little different. That was a lot of words. Let me pause there.

Catherine McDonald 19:34

Now I love it. Yeah, no, that’s it’s I mean, some of the mistakes that you talk about are I mean, they’re applicable to any leader really in any industry as well as the military things like just being overconfident because sometimes you feel you have to be confident that that’s part of the job that I have to look confident and not realizing that it’s okay to be you know, a little bit vulnerable around people you trust and ask questions and look for feedback. I’d say I don’t know, you know, all of these things. So you know, a lot of the things that you talk about, well, I remember, and I’m sure lots of people listening, you know, remember themselves doing as well. And I think what you talked about in terms of process improvement and finding lean and process improvement, that’s really interesting. And it would be interesting to hear a little bit more about that as well. Because I suppose from my perspective, when I started into lean and process improvement, similarly to you, I found it as sort of a way to look at this process and not the person, you know, we just kind of, you know, your relation to as well there that it becomes not about blaming a person or who did what didn’t do what it’s about, let’s look at our process together and work it out. So tell us a little bit about maybe your approach to that, and how you know, that or maybe other aspects of lean, maybe helped you to prevent, or at least reduce some of the mistakes that were being made early on in your career?

20:54

Yeah. So you know, I’ll bring this back to my to my very first project, if you will, when I was just getting into the training aspect of it. And it was a result of mistakes that were being made and leadership perceptions in an organization as as a as a Warrant Officer, I managed what what most known as a fleet management program, right, it was a field of vehicles that supported operations, think UPS thing FedEx, right, I took care of their parking lot of vehicles, if you will. And that required reoccurring maintenance. Well, the people that were using these vehicles, they don’t it’s, it’s, it’s a it’s a tool for them, right, it’s not a primary means it’s something that they use to do their primary functions better. And the maintenance of these was always, you know, a little bit tricky in the military, it always has been. But when, when the things don’t go wrong, they blame leaders, just just as I had been blamed, when logistics didn’t work, well, logistics would blame leadership, well, you’re not making sure the soldiers take care of their equipment you’re making, you’re not making sure that the drivers are taking care of their equipment. And no matter how many times I tried to change the people, it had no impact to the process that I was dealing with. And that’s where I started getting introduced, I heard somebody talking about process improvement. It was very interesting. They said, We’re going to stop focusing on people, and we’re going to focus on a process. And in my mind, I was like, what does that mean, you know, people process what’s all this, you know, gibberish that he’s talking about. And, and after about an hour and a half conversation, I was hooked. And I was like, I need more to I need to understand more of what you’re saying, How do I separate the person, because in my mind leadership at this time, again, mistakes that I made, I assumed that leadership not being present to enforce you know, processes to happen in my motor pools or in these fleet management areas was the problem was I started learning how to do root cause analysis and peel back that onion. And, you know, what impact do the leaders have? You know, what play? Do they have we process map to figure out how do they interact? We start understanding what impacts did they have to the individuals doing the task, I quickly learned that leadership didn’t even break the top 10 when it came to root cause analysis as to why processes were failing. That was how we managed paperwork. It was how we interacted with the people that were doing it and their ability to do the process, we asked them to do tasks without tools, right? That’s like me telling you to open the hood of your car, change the battery, and I’m going to give you a rubber band, right, we’re not MacGyver, it doesn’t work that way. And that’s where our processes were failing. So I started seeing mistakes and these mistakes. And what I realized was, again, the mistake wasn’t the person, it was the person standing there realizing that they couldn’t do what they were being asked. And all the leaders were doing was breathing down their neck saying do it faster, fail faster, is basically what they were telling them. And that’s how I started to approach everything. And when I would get into meetings with leaders, you know, whether I was in a leadership role, or there with others, and they would complain, this test didn’t get done, who’s who was responsible? I’d always raise my hand. I’m like, how about we redirect that question? Instead of asking, who is responsible? How about we asked why the process allowed them to fail in the first place? What did we miss? What guidance didn’t we give them? So they, you know, they went and my favorite thing that I tell everybody, when we very first start classes, I’m like, How many of you think you need process improvement in your life, and very few of them raise their hand because they’re new. So okay, how many of you sit in a meeting, and in this meeting, you have a big conversation about two hours, and there’s a lot of guidance given. And then when the meeting is over, you get up, you walk outside of the room, and then everybody that was in the meeting, as an external meeting in the hallway to discuss what the requirements were from the guidance you were given in the meeting, but now you’re dismissing the guidance giver. And everybody raises their hands. It’s the meeting after the meeting, to define what in there, that’s an indication that the process wasn’t given to you well enough to create an action. So now you’re going to go forward infer, and that’s going to lead to a mistake. But because you didn’t ask about the process, you’re going to be the one held liable for the mistake not the person that failed to give View clear and concise guidance. And that’s again, how I started molding my conversations and working with those that were below me when I came down. If something was wrong, I didn’t ask them why they did it wrong. I said, What guidance were you given to do this action? Did you feel it was clear and concise enough for you to execute whatever task it is, you’re being asked to execute? And what I always found very interesting, as I transitioned, that question worked in this industry as well, every manufacturer that I’ve worked with when I’ve gone out to their floors, or I’ve gone out in their shops, or I’ve sat down with their leadership, and I asked that same question. What’s the clear and concise guidance that you’re giving to avoid a mistake happening? We come across the same results are like, well, we told him to do something. But did you clarify something?

Patrick Adams 25:47

Yeah, I love it. And I love that your that your focus is so heavily on the process. And I think most people that understand, lean and have been involved in in continuous improvement for any time, hopefully, would, would be in agreement with you on that, that, that we need to focus on the process, not on the people when it comes to, you know, why problems are happening, why, why we’re having, you know, failures and things like that. I also want to ask you about the people side of things too, because there is a huge piece of this that does fall on to people development. I know we had Brian Tierney on from Seating Matters a few weeks ago, and he talked a lot about Lean being a people system, a people development system. And so I want to ask you to in the in the army, you know, as you started to move up in the ranks, and you, you know, became an NCO and then a Warrant Officer, I have to imagine that you while you were also working on process stuff, again, as you started to understand process improvement. You were also doing a lot of coaching, mentoring, training of soldiers. So what did that look like? And how has your process for mentoring people? How has that developed over the years? What would what would you say? Is your approach to developing or mentoring people in the right way?

27:48

Yeah, you know, and that’s such a great question. And you’re right, I do. I look at these into parallels I use Lean to help people not to blame people. Right? Because people are, I mean, they’re one of the pillars respects to people, right? It’s a pillar of lean, and it’s 100% accurate. And I, I focused on the people aspect and the leadership development by teaching those around me also how to look at processes to ask the question behind the person and make them understand. When we come down and something goes wrong, you want to you want to let the person know that mistakes are going to happen, right. And you know, human failure is just a way of life skills based knowledge based, you know, it doesn’t matter slips, slips, and lapses. Most know the common terms that exist in there. But if you understand mistakes, then you’ll understand not to use your role as a leader and understanding of process improvement, to blame them and ask them about their failures. You ask them about how the process could be better to support them. So the people side of it to me, and I think what shifted, you know, you’ll hear the term, you catch a lot more flies with honey, right? I look at lean as the honey, if I come down and say, hey, look, I understand things are happening. I’m here to make your process better. I’m here to make your life better. So you can learn from that. What my hopes are, that when somebody underneath them does something wrong, they want to initially jump to the reaction that it was an intentional mistake, a violation of some sort. So you know, people are 100% The reason that I do process improvement, you know, I am focused on the process improvement, but the largely from the aspect of supporting the people and keeping them out of fight, you know, keeping them out of the fire, for lack of better terms. And that’s where I developed as a leader. And what I found is when I stopped going into my boss’s office, and blaming people for the reason that we didn’t accomplish a task, and I came in to say, Listen, this is the process that didn’t work. Well, we can get the people to this point. It changed the dynamic with my leadership. And then I could go down as a mentor of the other and say, hey, look, we’re not you know, we’re not here to discuss your part of this problem. We’re here to discuss the process to let do that kind of thing. And when people saw me coming as I grew up when I was a young NCO, if somebody saw me coming, they would cringe, because they knew I was coming to yell at them. Because at that point, I didn’t understand the impact of my actions to them. And then what did they do when they started growing up to be leaders? Well, if I got yelled at as a leader, I’m going to yell as a leader. That must be how we do it. And as I started to look at processes as a way to support people, as opposed to yell at them, those below me started doing the same things. And they started taking on those, those attributes as well. And you would see it when as I grew from Echelon to Echelon in the military, those that I supported, changed how they interacted, I would tell them, you know, and then you know, what, what’s going wrong in your organization? What are you not getting? So it’s? I don’t know if that gets it. But that’s, that’s what we focus on is? The answer is the people. It’s not the question.

Catherine McDonald 30:56

Yeah. And I think some of what you’re saying is just, it leads me to think so you’re talking about, obviously, a mindset change for you over the years, you mentioned the word curiosity a couple of times, and I always look for curiosity on a scale, or a continuity, from judgment to curiosity. And it sounds very much like one of the things that you mentioned, as something you’ve learned over the years is to move from that judgment of people towards curiosity. And obviously, the whole area of lean and process mapping helps you to do that. But I think that’s really, really important for young leaders to understand that that’s a really important aspect of leadership is that we don’t go in and, you know, blame or judge that we always seek to understand and and you know, your points, you made those points very, very well. I’m also wondering how you mentor somebody. So a popular kind of our common issue that I would see what young leader is, is the jump from leadership, or the transition from sorry, a regular role as a team player into a leadership role. And sometimes what I see is people not understanding that it’s not all about them anymore. So it’s not about their performance, or what targets they hit, they now have to look at maybe success or achievements as as what the team achieved, not what they achieved. So I think that’s the same goes for anything you’re doing and lean or process improvement. But as a mentor, how do you work with people to help them understand, you know, help young leaders understand that it’s not about them anymore? It’s really is about your team? So what would you say to people to help them understand that?

32:23

It’s interesting, I actually have a process for that. Imagine that a process to help leaders right now. So first part of it is, is defining leaders and leadership, right? There’s there’s a difference there. Leaders are in charge. It’s a position of authority. Leadership is a quality, it’s something that we possess, that people gravitate towards. And when we move people from team members into these leader roles or leadership roles, and like I said, that term gets universally used, from my perspective, there’s a different aspect, you know, you’re assessing their ability to work in an authoritative position without overusing that authority, but you’re also looking at them from how are they perceived? That’s how I that’s how I personally kind of judge leadership, how are those that are around you react to you? Are they following you? Or are they opposed to what you say, you know, are you the guy in the room that they turn away from? Are you the guy in the room they turn to whether you’re in an authoritative position or not? And when I’m working with my will go back to the military for many young soldiers into young NCOs, and young worn officers in the seniors. The questions that I asked them are, do you understand the difference between the two of those? Do you understand how to separate the authority you have to make decisions from the leadership roles that you that you use inside of the organization? And just like you said, Katherine, how do you get them to understand is the team not the person, one of the processes, I asked him all the time, as I asked him, I’m like, list your list of the successes of the section of the unit that have happened over the last six months to a year. Now usually, we have to keep a running tally, because we have report cards, performance reviews, much like industry does, we have awards, they get submitted. So I’ll ask them list, this sections, your motor pool, for instance, or your units, achievements. And the next of those achievements, I want you to write down how much you directly contributed to those, and then how much others directly attributed to those or contributed to those. And when you start putting stuff on paper, and you start laying down all the things that lead to the success of a task and you start looking at names next to it. Well, we did these 35 things led to this end state and only five of them were I did I actually do are directly responsible for everything else where my team members, it starts to show them of 35 tasks you were five with 30 without those 30 You wouldn’t be successful or your leadership or leader role wouldn’t be as viewed as success because without your team you never would have got there. So anytime you walk into an action, something from an authoritative position, you need to break that down and understand where your team plays into the contribution into the section of that task. And then not only as an From the leadership perspective, know your part, but know how to support them and the things that they have to do as well. And that’s why when we grow as leaders, we take on multiple hats, if you will be the leader that makes decisions, but understand the leadership required to support them to make us successful. And you can almost, I won’t say, quantify that. But you can qualify that to an extent when you start looking at contribution of tasks to completion. And that’s kind of how I started bucketing things in my head. Yeah,

Patrick Adams 35:29

yeah, I like that. I like that. I’ve never heard that be put, or that exercise the way that you do that, and I might have to steal it. Because I really, I really liked the idea of visually seeing that and, and writing up the tasks and putting names and then using that as a way to explain, you know, leadership versus lead. Well, the the position of leadership versus your quality of leadership. I love that. So thank you for that. It’s good.

36:00

That you added to that as well. Like, let’s talk about process improvement. When you know, some people ask, Well, how do you lay out? A lot of the soldiers or leaders now that I work with the organizations I work with? They’re like, Well, how do you define those? What’s very simple, what adds value to the process that you’re trying to get to, which leads us to discuss what constitutes value added and what doesn’t. So it just digs in. That’s where process improvement links into this leadership aspect. We use our process improvement language, if you will, as a way to size that out. Right,

Patrick Adams 36:31

right. Yeah, that’s good. And I have to imagine that in the 24 years, you were in the army, and then now afterwards, continuing to work with soldiers and and other young leaders, not just in the military. But outside of that, I have to imagine that you’ve been able to witness and even mentor young leaders through their mistakes. You know, you’ve mentioned a couple of different ones. But can you expand on that a little bit, and maybe even given us give us some examples of some of the leaders and what their mistakes? Were maybe just the top mistakes? I’m sure you’ve experienced a lot. But what are some of the top mistakes that you see young leaders making? Yeah,

37:11

you know, it’s so especially, you know, moving past the military industry, because it is a very different dynamic, you know, with the military. part aside, leadership, again, does come with this hierarchy, that’s very well known, but that doesn’t exist in industry. And when I, when I worked with some of these department managers, and I worked for some of those that are employees that are coming up through in there, a lot of the mistakes that you’ll that you’ll see they parallel, but it’s almost an unstable ground, you know, a confidence soldier is almost a given a confident employee is is interesting, because there’s like, there’s almost this false confidence that you see, they want to be perceived as confident, but they’re really kind of lost in the middle a little bit. And again, so what they’ll do is they’ll try to over over perform, I always kind of tell everybody not to parallel this back to the military. But in the military, were very team oriented. When I moved from one unit to the next unit, I’m already on the team, just by the virtue of me being a soldier, I’m accepted in day one, just like that. Industry, I don’t see that in industry, you have to earn your way into that team, which means you have to earn your way into those roles. Which means when you get into them, there’s this perception from what I’m dealing with an industry where they feel that they have to have all of the answers in the military. I’m not afraid to ask an industry I am. Because if I start asking questions, somebody around me is going to question whether or not I belong in that role. And what if do I have what it takes to succeed in that area? So a lot of the mistakes that I see are the same ones I made as a young soldier overconfident making assumptions, filling in blanks. And you’ll see them say, well, I’ll ask one example. I work with a company right now. And there is trying to think of make sure I don’t mess up the NDA, the company has a very specific process as you move up, right, they they bring seasonal workers on and they develop them, and then they bring them into full time hires, and then they develop them. And then they actually become into the leadership roles for each of these different functions inside of the factory. And then there is in one of those pivotal moments where they’re bringing some of their full time workers into management roles as some people are moving out of state. And that, you know, the mistakes that you see being made is when they get into that role. They still think like they’re on the team, as opposed to in charge of the team and they have trouble making that distinction. A lot of that is because they’re being promoted from within. And there’s a lot of organizations were like, well, if they’re good at this job, that must mean they’ll be good at the next job as well. And assuming that, you know, the business makes the mistake assuming that they know how to function at the next higher level. The person makes the mistake of thinking that there’s there when that when they will make the mistake of thinking they make the mistake of not understanding what the next role requires. So they would get into that role. And they just try to do that part better, and they don’t take the time to start to understand well, okay, now that I’m in charge of the team members and not just the team member, what are the additional things that I have to do and they so they just start again making those assumptions filling in those blanks. So we have to get them again to sit down and understand like, hey, what, what is it you think you’re responsible for? What processes do you manage now in this leadership or management position? And usually, when I get these young leaders in industry, they don’t have an answer to that question. So then again, I go back to their leadership and say, hey, when you promoted them into this position, did you define and clarify what your expectations were. And again, usually, if it’s anything at all, it’s very ambiguous. Because other will know they watched the person that you know, they’ve been here, they’re here long enough to know what’s happening in this organization, we always shouldn’t have to keep telling them, we promoted them because we believe they can do better. Okay, but again, your mistake to not clarify is now translating into their mistake on the floor, which is now costing you quality, which is costing you money. That’s the largest mistake is the continuity and consistency and clarity from the top to the bottom. In in expectation, management and execution.

Catherine McDonald 41:15

You mentioned some of the mistakes, more of the mistakes there fail. And yeah, I’ve seen it as well, you know, overconfidence sometimes under confidence, sometimes it’s lack of skills that could be related to emotional intelligence skills, like communication, conflict management, could be could be anything different people are different, and different leaders, you know, have different skill gaps. And you said something interesting, we have to got to get people, you know, to sit down and think about this, think about, what am I doing well as a leader, and where are these gaps? And, you know, I agree that I don’t think that happens enough. I think leaders are young leaders are put into these positions, and it’s all about what do I do? You know, what does my to do list look like? Here’s all the work you have to get through. But what should your leaders do to really step back sometimes, and do more of that more introspection, you know, grow their self awareness of who they are, and and how they are as a leader? How can what what advice would you have for young leaders to kind of build more of that into their professional development?

42:12

Yeah, you know, it’s that’s such a great question, too, you know, in my opinion, it’s, it’s, sometimes leaders will think that the only way to get ahead is to work extra, and they take on extra stress. And so they sit at home. But when they sit at home, and they try to answer those questions by themselves, they’re not going to come up with the answers again, a mistake that they make is thinking that they have the ability to conjure something from nothing. So the answer to the question may feel like the wrong thing for them, it’s sitting back down with your team, when you get into that leadership perspective. It’s not them figuring out it on their own. And it’s going to have to fold you’re going to sit down with the team. What do you expect from the leader of this team? What in your mind, I would be asking those underneath me like, hey, you know, let’s just, we’re just Phil, Katherine and Patrick, right now we’re not Sergeant chief or Sam, sir, or ma’am, or boss, or whatever it is, let’s just have this conversation, get them away. First off, get them away from the organization, get them outside of the building. So you don’t you don’t have those those roles associated with, you know, let’s, let’s go somewhere else, go to breakfast, or go to lunch. And then part of answering the question of what I what I think I should be doing as a leader is to understand what my team expects of me, as a leader in that role, I don’t want to talk about what the person did before me here, I want to talk about what a leader is in your mind that supports your day to day tasks. And then, you know, start making those assessments and we can become self aware, understanding what the people’s requirements are starts to allow me to answer in my head, do I? Do I meet that requirement? Or do I not meet that requirement? If I don’t, I can ask the team for more clarity, because my leadership is ultimately going to lead to their success. So the answer in my opinion for them is to not to self isolate, and figure it out and get into this isolated silo, it’s to get back with your team and open up, figure out what those what those things are from their perspectives, you know, the fine balance that is reminding them that at some point, leader, leader decisions have to be made, but at least they should be made off of, hopefully, understanding what their requirements are. So it’s, it’s more communication, not less communication.

Catherine McDonald 44:24

Do you think the one to ones are really important as well there with your manager, just time to just stop? I agree with you go into a team getting feedback, hugely important, but I also think that time and space where someone’s just asking you powerful questions, has your own manager has a good, you know, coaching approach, and you have time to just stop and think about these things as well. It’s probably I think, important too, would you think?

44:47

Oh, absolutely. Absolutely. You know, it’s you look at research methods when you don’t know anything you ask the masses, when you have some pretty good ideas of what it are you start isolating on the people and it’s the same thing. Get the ideas from the masses, but yeah, the one on one ones are, are, are imperative. I mean, I’m not even sure that’s an option at this point because you know, you can’t get to a clear and concise answer, unless you isolate the conversation. And in those one on ones give that and hopefully by that time, the one on ones, make the team members comfortable enough to tell you the good and the bad, right? If they see in a team environment that you’re not out there as judgmental, again, you know, one of the things we always tell them be curious, not judgmental, that’s a sign of good. And that’s when they see that there’s curiosity. Hopefully, when they come in for the one on one, though, they know they’re not being judged. And what we are looking for is real feedback. But you get an opportunity to say things you might not say in a team, right? Because the team members, you know, while they’re judging the while we’re having a conversation focused on leader or leadership, they’re judging each other. It’s just human instinct. So yeah, getting people separated, and really given them a chance to unveil a little bit. Oh, absolutely. I would agree. 100%.

Patrick Adams 46:00

That’s great. And speaking of teams, I want to shift gears just a little bit here, as we as we wrap up the the episode today, Phil, but speaking of teams, you have raised your hand to, to be in and not not just to be in attendance for the Lean Solution Summit coming up on September 24 25th, and 26th. But also, you’re putting together in an elite team of military veterans or active duty, I guess, too, but my understanding is you’re putting together a team to compete in the Lean competition at the summit, this will be a new addition to the summit this year. I’m really excited about it, there’s going to be four teams that compete against each other with different simulations. And it’s going to be pretty amazing. But I think you’re still looking for members to add to your team. Is that right?

46:49

I am. So yeah, if you’re listening, you’re a veteran, your active duty, any three of the compos, any branches of service, it doesn’t matter? We are I would, I would be very easy with the word elite, we’re putting a team together, we’ll see the elite, you know where that comes down the road? Right? We have different challenges, right? We’re not all in the same organization. So we have two hurdles to cross one is making sure that we’re prepared for the for the scenario, but we have to learn who we are, as well don’t all work for the same organization. But yeah, absolutely. We are definitely looking for that 10 person team, I think was a number that you pegged on the board for us and anybody that’s watching that is interested, you know, I’m sure the contact information will come up somewhere. But I would love to hear from anybody that is interested in it. And I think it’d be, I think would be very good for veterans and active duty or anybody that served it’s a very what made me raise my hand so quickly wasn’t, you know it, the cop was on his competition in me. But past that, as the experience this bringing together is going to get to see something that we don’t typically get a chance to see. So it’s only after you’ve transitioned for years that you start to understand how to be a civilian again, right now. So a lot of these early transitioners in active duty. I’m just super excited to bring them in, not just to the competition, but into the summit environment alone to understand a different view of the world. Yeah,

Patrick Adams 48:10

well, I’m excited to have have your team represented at the summit and also to have lien Alaska represented at the summit. We’re excited for that in and if people want to get a hold of you, if they want to learn more about Lean Alaska, what’s the best way for them to contact you? And we’ll make sure that we throw that in the show notes as well. Yeah,

48:31

you know, LinkedIn is probably the best social media platform just find me Phil rank or lien Alaska is on there. I regularly stick with that past that, you know, emails or emails are great, but they’re kind of weeding themselves out a little bit. So yes, typically, LinkedIn is the best way or you can go to our website, which will direct you right to me as well. The alaska.com really original I know.

Patrick Adams 48:54

Awesome. Any last, there was one more thing you wanted to mention to veterans before we close out today? Can you want to throw that out there? And then again, we’ll throw some some information in the show notes as well on that.

49:05

Yeah, for you know, for veterans for active duty, you know, benefits, they start to trail as we go along. When we’re on active duty, we have access to so many benefits, it’s not even funny. As we become veterans, they become smaller and smaller. And the longer you’re a veteran, the less that there is, you know, we spent a lot of time in the military are focused on our mission. But we also have to know they tell you there’s two things that are constant in life death and taxes. Well, I got a third one is retirement is going to happen. Whether you like it or not, you will leave the military, it will prepare yourself for that and then use the benefits to prepare for that in doing so. I’m in the position that I’m in not because I figured it out when I retired but because I use the army to get me here. I used it as a training ground to understand process improvement. I use it as you know, a way to understand how to operate and then figure out what that meant as I got older my career and industry and now I’m making that transition and I’m still transitioning, but the point was the Army gave me my start. And it did that for a lot of folks. The problem is a lot don’t understand the benefits that are out there. So I will tell you look into your benefits credentialing assistance is available to any active duty Army, Air Force and Coast Guard have phenomenal credentialing assistance, training programs that have more than enough benefit for you to build into some of these credentials and certifications to support yourself getting over Marines and Navy also, again, have cool programs, which do very well for credentialing examinations, look into whatever branch of service whatever combo, active duty reserve guard, take, take. Take advantage of these because when you’re a veteran, then you start getting limited by GI Bill. GI bill is not accepted by as many when it comes to credentialing as well. So again, that pool starts to get smaller and smaller. So yeah, my note to anybody, whether you’re in the military been in the military connected, if you just know somebody bumped into you one time and have their phone number. Getting those benefits used, while they’re in will, will be that path to success, because I’m here to tell you one thing that I found, industry loves military leadership, they love the leadership that’s built into us what they don’t love is the lack of experience that we have, understanding how that works in industry. So when you get these industry recognized credentials, it’s kind of your window into the future. So sooner, the

Patrick Adams 51:24

better. Yeah, that’s great. Great advice, Phil. Phil, thank you again, for being on with us. Really good conversation. I think we probably need to have you back on the show again, to dive into a couple other areas, too. I mean, the experience that you that you provided today was was really great. So thank you very much for that.

51:42

Oh, thanks for having me. This is Bob. I’ll come back anytime. I love this. This

Patrick Adams 51:46

is great. All right. Have a great week.

0 Comments